• Articles

'A splendid night; the moon shines with extraordinary brilliancy, silvering the surface of this lovely river, bordered by high mountains, looking like a grand and gloomy rampart. The chirp of the cricket alone breaks the stillness.'

- Henri Mouhot wrote in his diary on the 15th of July 1861 while sitting at the base of a tree in dense jungle on the bank of the mighty Mekong, near the ancient Laotian capital of Luang Prabang.

(End Note 1)

In the footsteps of Henry Mouhot,A French explorer in 19th Century Thailand, Cambodia and Laos

———

Dawn F. Rooney

Author's note: In 1997, I was so moved when I visited the site where Henri Mouhot was buried that on returning to Bangkok, I re-read his diaries. I was intrigued by this extraordinary human being, and felt compelled to reflect upon the little-known man. For nearly three years, from 1858 until his death in Laos in 1861, Henri Mouhot explored the inner regions of Thailand (known as Siam at that time), Cambodia and Laos. His legacy is a detailed and unfinished diary of his keen observations of the places, people, animals, insects and shells of the region. Some of his notes are the earliest surviving records of previously uncharted areas.

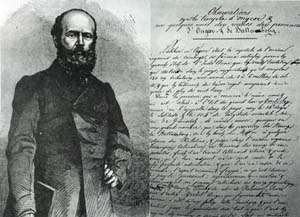

Alexandre Henri Mouhot was born on 15 May 1826, in the French village of Montbeliard, near the Swiss border. His father served in the administration of Louis Philippe and the Republic and his mother was a respected teacher who died when Henri was twenty years old. They had one other child, a son, Charles. Both parents made sacrifices to provide for the education of their two sons. Henri was a Greek scholar and studied philology with the intention of teaching but he also developed interests in the natural sciences and foreign travel at an early age.

When he was eighteen, he went to St. Petersburg where he taught French and Greek at the military academy, and later received a professor's diploma. Mouhot, who had a facility for languages, quickly learned Russian and Polish. In his leisure, he studied and mastered a new photographic process invented by Louis-Jacques-Mande Daguerre. He took pictures of landscapes, distinguished people and places of architectural interest. At the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1854, Mouhot left Russia and returned to his home in Montbeliard.

A historical link between Russia and Montbeliard may explain why Mouhot decided to go to Russia. The principality of Montbeliard was one of the sovereign states of the Germanic Empire in the mid-18th century. In 1776, the future Czar Paul I of Russia married Sophia-Dorothea of Wurttemberg, Countess of Montbeliard and great-niece of the King of Prussia. Although the countess lived abroad, she remained loyal to her birthplace and returned to it often. This historical link was the catalyst for many natives of Montbeliard to go to Russia as private tutors or soldiers in the mid-19th century.

(Drawn by M.H. Rousseau, from a PhotographAfter a short stay with their father in Montbeliard, Henri and his brother, Charles, travelled through Germany, Belgium and northern Italy, introducing the Daguerre photographic process through their works of art. The two brothers moved to England in 1856 where they both married descendants of Mungo Park, the famous Scottish explorer of Africa. Henri married Annette, who was probably the granddaughter of Mungo Park. The two families settled on the island of Jersey in the English Channel where Henri refined his study of the natural sciences, specialising in ornithology and conchology, and renewed his interest in foreign travel.

Mouhot, an educated and cultured gentleman of the mid-19th century, seemed an unlikely person to want to explore the remote interior regions of South-East Asia. Some two years after moving to Jersey, however, Mouhot set out alone for the east. He sought financial support for his travels from both France and England but was unsuccessful. The prestigious Royal Geographical Society in London, though, did give him its backing which undoubtedly boosted his confidence and spirits as he sailed east to a region so vaguely known at the time that it was described on some European maps of the period as 'Beyond India'.

It is unknown what influenced Mouhot to travel to the orient. Historians have put forth several factors. He may have been fulfilling a long cherished dream to travel to Asia; or his concentration on natural history when he moved to Jersey may have stimulated his interest in acquiring unique specimens from the east; or, perhaps, a book, The Kingdom and People of Slam: with a narrative of a mission to that country in 1855 by Sir John Bowring, published in 1857, may have inspired Mouhot's journey. Another possibility is that he was influenced by the increasing French presence in South-East Asia in the mid-1850s and the extended territorial rights of the French to Cochin-China (south Vietnam) and Cambodia.

On 27 April 1858 Henri Mouhot and his King Charles dog, Tine-Tine, sailed from London for Bangkok, a journey that took four months. Soon after arriving he met Bishop Pallegoix who put him in touch with other French Catholic missionaries serving at interior posts. They offered him food, shelter and solace, during which time he wrote poignantly of his respites with these missionaries: '... have you suffered? If you have, you will appreciate the feelings with which the solitary wanderer welcomes the divine cross, the heart-stirring emblem of his religion. It is to him a friend, a consoler, a father, a brother; at sight of it the soul expands, and the more you have suffered the better you will love it. You kneel down, you pray, you forget your grief, and you feel that God is with you. This is what I did.' (EN 2)

His beloved dog also afforded him comfort and companionship. 'My little "Tine-Tine" says nothing, but creeps under my counterpane and sleeps at his ease... I much fear that my poor dog will come to an untimely end, and be trampled under foot by some elephant, or devoured at a mouthful by a tiger'. (EN 3) Tine-Tine ironically outlived his master. When the French Mekong expedition visited Luang Prabang, six years after Mouhot's death, they found the dog in the care of a Laotian family.

Mouhot used many modes of travel - fishing boats plying the coastline, elephants, surefooted horses for mountainous areas, oxen carts and, often, he trudged through the jungle on foot. He slept in a hut when he could, but his accommodation was usually a hammock strung between two trees and a mosquito net. He even spent one night in a tree when he was exploring a mountain range and lost his bearings while chasing a wild boar.

Angkor Wat at dawn The preservation of Mouhot's diaries, illustrations and specimens can be attributed to a fortuitous trip he made to the coastal town of Chantaboun (Chantaburi) where he met one of the two boys who became his travel attendants, and who packed up his materials and carried them from Luang Prabang to Bangkok after Mouhot's death. Upon arriving in Chantaboun, a Chinese pepper planter offered food and lodging to Mouhot. The planter, a widower, suggested that his eldest son, eighteen-year-old Phrai, become Mouhot's servant. Phrai was 'a good young man, lively, hardworking, brave, and persevering...Born amidst the mountains, and naturally intelligent,...he fears neither tiger nor elephant. All this, added to his amiable disposition, made Phrai...a real treasure to me'. (EN 4) The other servant with him at his death was Deng ('the Red'), who spoke some English. 'He is very useful to me as interpreter, especially when I wish to comprehend persons who speak with a great piece of betel between their teeth. He is likewise my cook, and shows his skill when we want to add an additional dish to our ordinary fare.. .This attendant of mine has one little defect, but who has not in this world? He now and then takes a drop too much'. (EN 5)

In the spring of 1859, Mouhot left Chantaboun in a fishing boat and followed the coastline along the Gulf of Siam to Kampot, on the west side. The First King of Cambodia (Ang Duang, reigned 1848-1860) was in residence and granted an audience to Mouhot, who presented the king with an English 'walking-stick gun.' The king reciprocated by giving Mouhot permission to travel to the capital of Udong, an eight-day journey to the north-east by oxen. There Mouhot met the Second King of Cambodia (Norodom, reigned 1860-1904) who provided him with wagons and elephants to continue north to the village of Pinhalu where he visited the Stiens, a savage tribe occupying an area east of the Mekong.

During the following winter, Mouhot began the part of his journey that he is most well-known for in the west - his exploration of the ruins of the ancient Khmer capital of Angkor. From Phnom Penh, he followed the river north and noted that 'the river becomes wider and wider, until at last it is four or five miles in breadth; and then you enter the immense sheet of water called Touli-Sap [Tonle Sap], as large and full of motion as a sea . . .The shore is low, and thickly covered with trees, which are half submerged; and in the distance is visible an extensive range of mountains whose highest peaks seem lost in the clouds. The waves glitter in the broad sunshine with a brilliancy which the eye can scarcely support, and, in many parts of the lake, nothing is visible all around but water. In the centre is planted a tall mast, indicating the boundary between the kingdoms of Siam and Cambodia'. (EN 6)

The centre west entrance, Angkor Wat (Drawn by M. Theroud from a Sketch by Mouhot) Numerous western missionaries either saw or knew of Angkor at least three hundred years before Mouhot. A text by Portuguese Diogo de Couto of the mid-16th century, for example, accurately described both Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom. Later, Spanish missionaries wrote of the ruins at Angkor. Pere Chevruel, a French missionary, wrote at the beginning of the 17th century: 'There is an ancient and very celebrated temple situated at a distance of eight days from the place where I live. This temple is called Onco, and it is as famous among the gentiles as St. Peter's at Rome.' (EN 7) The above mentioned accounts of Angkor received little attention in the west, perhaps because they were religious records and were not circulated. So even though Henri Mouhot did not 'rediscover' Angkor, as has been the long-held idea in the west, he was the first westerner to generate a widespread interest in the ancient Khmer capital of Angkor. He did this through his diaries which contain detailed descriptions and illustrations of the Khmer monuments.

Mouhot's first impressions of Nokhor, or Ongcor [Angkor] testify to his astuteness and perceptiveness. 'In the province still bearing the name of Ongcor,...there are,...ruins of such grandeur, remains of structures which must have been raised at such an immense cost of labour, that, at the first view, one is filled with profound admiration, and cannot but ask what has become of this powerful race, so civilised, so enlightened, the authors of these gigantic works? One of these temples -a rival to that of Solomon, and erected by some ancient Michael Angelo - might take an honourable place beside our most beautiful buildings. It is grander than anything left to us by Greece or Rome...' (EN 8)

Although Mouhot visited and described several monuments at Angkor, it is his perceptive observations and drawings of Angkor Wat that captured the imagination of the west. They include the layout of Angkor Wat, architectural features of the terrace, the causeway, roofs, columns, porticos, and galleries and details of thebas-reliefs - scenes, locations, dress, jewellery, military weapons, flora and fauna. 'What strikes the observer, ... [apart from] the grandeur, regularity, and the beauty of these majestic buildings, is the immense size and prodigious number of the blocks of stone of which they are constructed.' (EN 9)

In the summer of 1860, Mouhot set out on another pioneering journey, this time to north-eastern Siam and Laos as far north as Luang Prabang. Before his departure, Siamese in Bangkok told Mouhot that they knew of only one other foreigner in the past twenty-five years, a French priest, who had penetrated the heart of Laos and returned safely. Mouhot, though, believed it was his destiny to make the trip. First he went north to Ayutthaya, then to Korat where he visited a Khmer temple, Prasat Phnom Wan, and on to Chaiyapoon, where his trip was aborted by an official who refused to help him obtain oxen or elephants for his journey. So he returned to Bangkok for additional credentials and then continued to Laos.

He reached Luang Prabang on 25 July 1861. The mountains which, above and below this town, enclose the Mekong, form here a kind of circular valley or amphitheatre, nine miles in diameter, and which, there can be no doubt, was anciently a lake. It was a charming picture, reminding one of the beautiful lakes of Como and Geneva. Were it not for the constant blaze of a tropical sun, or if the midday heat were tempered by a gentle breeze, the place would be a little paradise.' (EN 10) Mouhot collected numerous specimens of insects. A splendid black insect that he discovered in Laos is considered one of the most magnificent known specimens of a beetle. It was named Mouhotia gloriosa, in honour of Henri Mouhot.

He planned to spend the remainder of the year in the environs of Luang Prabang, then go to the Laotian tribes to the east in early 1862, and in July or August, to go down the Mekong to Cambodia. His plans, though, were aborted when on 19 October 1861 Mouhot was attacked by a fever. His notes leave little doubt that he himself thought he was near death. 'If I must die here, where so many other wanderers have left their bones, I shall be ready when my hour comes'. (EN 11) Ten days later he made his last entry in his diary,'- Have pity on me, oh my God....!' (EN 12) Henri Mouhot died on the evening of 10 November 1861.

Phrai and Deng, Mouhot's faithful servants, buried him on the bank of Nam Kan River, east of Luang Prabang, at the spot where he died. Then they carried his notes and specimens to Bangkok where they transferred the items to the French Consul who forwarded them to Mouhot's wife and brother. The family later gave them to the Royal Geographical Society in London, where his hand-written notes are accessible in the archives today.

Six years after Mouhot's death, the French Mekong Exploration Commission set out to find a navigable route, from Saigon into China, that could be used for trade along the Mekong River. The expedition, led by Commander Ernest-Marc-Louis de Gonzague Doudart de Lagree, a 42-year-old naval officer, used the map drawn by Mouhot for travelling overland in Laos. As his map was the only existing one at that time, credit is given to Mouhot for having produced the first map of the route from Bangkok to Luang Prabang.

The Admiral in charge of the expedition, de la Grandiere, believed that France owed 'recognition and regret to the hardy explorer to whom she had granted neither help nor encouragement when they could have been of use'. (EN 13) He, therefore, requested that the Doudart de Lagree expedition try to put up a monument in Mouhot's memory near the site where he died.

On 29 April 1867, the commission reached Luang Prabang. Soon after arriving, Commander Doudart de Lagree asked the ruler of Laos for permission to construct a monument over Henri Mouhot's grave. The ruler readily agreed and offered to provide the necessary materials. Louis Delaporte, a member of the commission, made drawings and supervised the building of the monument. It was placed on the spot where Mouhot was buried, high on the bank of the Nam Kan River. A simple plaque inscribed 'H. Mouhot, May 1867' was attached to the monument. The date of 1867 refers to the year the French commission erected the tombstone.

Henri Mouhot's tomb, Laos, 1997. The plaque on the south face of the tomb A detail of the plaque on the north face of the tomb The plaque on the west face of the tomb A member of the expedition wrote: The landscape which surrounded the tomb was pleasant and sad at the same time. A few trees and the rustling of their tops accompanied the murmur of the waters of the Nam Kan which ran at their feet. On the opposite side rose a wall of blackish rocks which formed the other side of the torrent. There are no dwellings and no human traces in the vicinity of the last resting place of this adventurous Frenchman.' (EN 14)

The next French expedition to record seeing Mouhot's monument was on a mission to find out about the political environment in the territories between Luang Prabang and Tonkin. Dr. Neis, a medical doctor, led the mission and visited Mouhot's tomb in 1883. He decided to go to Mouhot's tomb to see what had become of the monument which had been erected for our compatriot by the de Lagree Mission and to have it repaired if necessary. He wrote : 'Early in the morning of the twenty-seventh I left on horseback, accompanied by my young interpreter and two lower ranking mandarins. After having crossed beautiful rice-fields terraced on the sides of the mountain range which followed the Nam Kan, we arrived, after an hour and a half of marching at a great and rich village called Ban Penom. There we commandeered the village chief and three or four Laotians to serve as guides and to open up the path for us. From these village there are only vaguely indicated paths and these men preceded us, to cut the branches which barred the route, with their sabers ...

After following the Nam Kan for an hour since our departure from Ban Penom, we arrived at the foot of a rather high mountain, the Pou So-uan, close to big rapids which are called Keng Noun and we made a stopover in a small Laotian hut built close to the river. The owner told me he had helped Mouhot's men bury their master and he proposed to take me to his tomb. We left our horses there and the locals cleared the path for us with sabers, cutting through lianas and rattans. After twenty minutes of counter-marching and groping our way, the guide pointed me to a thicket, saying; 'There is the tomb of the falang" [foreigner]. They attacked the thicket with blows of their sabers and, indeed, I soon found some scattered bricks on the ground: these were the only vestiges of the monument built by Mr. Louis Delaporte. Built in a humid forest, during the rainy season, the tomb had never been able to dry and the poor quality lime of the country had immediately been washed away by the diluvial rains common in this season. Above the grave the terrain had caved in. The bricks, no longer retained, fell one next to the other. Perhaps also the inhabitants of the surroundings or oarsmen on the Nam Kan had come to take away some of the bricks to make their kitchen ovens. Despite my search I could not find the sandstone plate which had the inscription. I had the soil carefully cleared from shrubs; I reassembled the bricks; then, remembering that Mouhot was a devout Catholic, I had two young trees cut to make a cross on which I engraved his name. Planted deep in the soil and supported by bricks, it will, at least for a few more years, indicate the place where the first European who arrived in Luang Prabang, was buried'. (EN 15)

Epilogue : The monument that stands today was put up by August Pavie, the first French consul at Luang Prabang, in 1887, to replace the first, less durable, one. Three plaques on the monument commemorate Mouhot. The one on the north face, inscribed with Mouhot's name and the dates of his birth and death, was put up by Pavie. Another one, on the south side, acknowledges both of the French delegations who erected monuments. It is inscribed, 'Doudart de Lagree...fit elever ce tombeau...en 1867...Pavie... le reconstruisit...en 1887.' [Doudart de Lagree raised this tombstone in 1867; Pavie reconstructed it in 1887].

The third plaque was put up nearly 130 years after Mouhot's death, perhaps as the completion of a longtime commitment. Upon hearing of his death, the Society of Montbeliard - where Mouhot was born - wrote in a letter to his brother 'His work was left unfinished, but it was gloriously commenced, and his name will not perish!' (EN 16) In 1990, residents from his birthplace of Montbeliard in France fulfilled this commitment when they travelled to his grave in Laos to pay their respects and to install a plaque on the west face of the tombstone. The inscription: 'La ville de Montbeliard...fiere de son enfant [the village of Montbeliard is proud of their child]... 1990.'

In August 1997,1 visited the tomb of Henri Mouhot. I wanted to see the last resting place of this extraordinary Frenchman, who went nearly two years without encountering another European. He risked his life in pursuit of nature and of 'seeing so much that is beautiful, grand, and new' in the remote interior of Laos which no other foreigner had seen before him. I wanted to see the environs of Luang Prabang, the treacherous river swirling through the thick jungle that Mouhot poignantly described in his diaries.

I went at the height of the wet season. A torrential rain during the night had left the early morning air still and sticky. The site seemed little changed from Mouhot's descriptions in his diary, although the access has improved. A low layer of mist floats above. We descended a steep bank to the edge of the swelling Nam Kan River, where muddy water splashed over the foot path. Perspiration rolled down our faces and soaked our clothes, prickly thorns pierced us as we plodded through thick jungle and gooey mud along the river's edge, which ran parallel to the river. A slight clearing in the jungle and a ray of sun, highlighting the bank, took our eyes to the steep slope of the bank nearest to us. In the distance, some twenty or thirty yards beyond, we glimpsed a corner of the monument that marked the last resting place of Henri Mouhot. The rest of it was hidden by thick jungle.

We began our ascent to the monument, and as we moved closer, it came into full view. Face to face, the rectangular, grey granite monument was bigger than expected (dimensions: height =10 ft; width = 6 ft; diameter =3 ft). We walked around it slowly, pushing bushes aside, reflecting on the brief life of Henri Mouhot (he died at age thirty-five), the contribution he made, the legacy he left in the form of his diaries, which were published posthumously (in English in 1864), and the dedication made by his wife and brother. The diaries were dedicated To the learned societies of England, who have favoured with their encouragement the journey of M. Henri Mouhot to the remote lands of Siam, Laos, and Cambodia.' (EN 17)

All illustrations supplied by Dawn Rooney

Notes

1 Mouhot (1864) Oxford University Press (reprint 1992), vol 2, p 141.2 Mouhot (1864) Oxford University Press (reprint 1992), vol 1, p 182.

3 Mouhot (1864) Oxford University Press (reprint 1992), vol 2, pp 94-5.

4 Mouhot (1864) Oxford University Press (reprint 1992), vol 1, p 155.

5 Mouhot (1864) Oxford University Press (reprint 1992), vol 2, pp 78-9.

6 Mouhot (1864) Oxford University Press (reprint 1992), vol 2, p

272.7 Clifford (1904) White Lotus (reprint 1990), p 154.

8 Mouhot (1864) Oxford University Press (reprint 1992), vol 1, pp 278-9.

9 Mouhot (1864) Oxford University Press (reprint 1992), vol 1, p 299.

10 Mouhot (1864) Oxford University Press (reprint 1992), vol 2, p 137.

11 Mouhot (1864) Oxford University Press (reprint 1992), vol 2, p 99.

12 Mouhot (1864) Oxford University Press (reprint 1992), vol 2, p 160.

13 De Carne (1872) reprint White Lotus (1995), p 152.

14 Garnier (1868) reprint White Lotus (1996), p 302.

15 Neis (1884) reprint and translation 1997, pp 73-4.

16 Mouhot (1864) White Lotus (reprint 1986), Memoir of the Author, J.J. Belinfante, p 27.

17 Mouhot (1864) Oxford University Press (reprint 1992), vol 1-, p7.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barren, Sandy, 'Back to the Future,' The Nation, 19 May 1996.Bowring, Sir John, The Kingdom and People of Siam, London, 1857; reprinted Kuala Lumpur and Singapore, Oxford University Press, 1969 and 1989.

Clifford, Hugh, Further India: Being the Story of Exploration from the Earliest Times in Burma, Malaya, Siam, and Indo-China, reprinted Bangkok, White Lotus, 1992.

Cooper, Robert, 'Henri Mouhot's travels in Siam (1858-1861),' Living, December 1983, pp 14-18.

De Carne, Louis, Travels in Indo-China and The Chinese Empire, Longon, Chapman and Hall, 1872, reprinted Bangkok, Cheney, White Lotus, 1995.

The French in Indo-China: With a narrative of Garnier's explorations in Cochin-China, Annam and Tonquin, reprinted Bangkok, Cheney, White Lotus, 1994.

Gamier, Francis, Travels inCambodia and Part of Laos: The Mekong Exploration Commission Report (1866-1868) -Volume 1, Walter E.J. Tips, trans and Intro, reprinted Bangkok, White Lotus Press, 1996.

Hoskin, John, 'In An Explorer's Footsteps,' Sawasdee, n.d. pp 43-45.

_______, Trailing an Explorer in Cambodia,' The Asian Wall Street Journal, 4-5 August, n.d.

'Montbeliard and Holy Russia, an unusual history,' Internet site <http://www.cicv.fr/FC/RUSSE/histgb.html>, 10 Dec 1997.

Mouhot, Henri, Travels in Siam, Cambodia and Laos 1858-1860, London, John Murray, 1864, 2 vols, reprinted Bangkok, White Lotus, 1986; reprinted Singapore, Oxford University Press, 1989 and 1992.

Neis, P. Travels in Upper Laos and Siam: with an Account of the Chinese Haw Invasion and Puan Resistance, Walter E J Tipps, trans and Intro, reprinted Bangkok, White Lotus Press, 1997.

Osborne, Milton, River Road to China: The Search for the Source of the Mekong, 1866-73, 2nd edition, Singapore, Archipelago Press, 1996.

Ponder, H.W., Cambodian Glory, Condon, Thornton Butterworth, 1936.

Pym, Christopher, ed, Henri Mouhot's Diary, Kuala Lumpur, Oxford University Press, 1966.

Smithies, Michael, Intro, Descriptions of Old Siam Kuala Lumpur, Oxford University Press, 1995, pp 182-189.

Top